Glory days. 1974

By Mike London

Salisbury Post

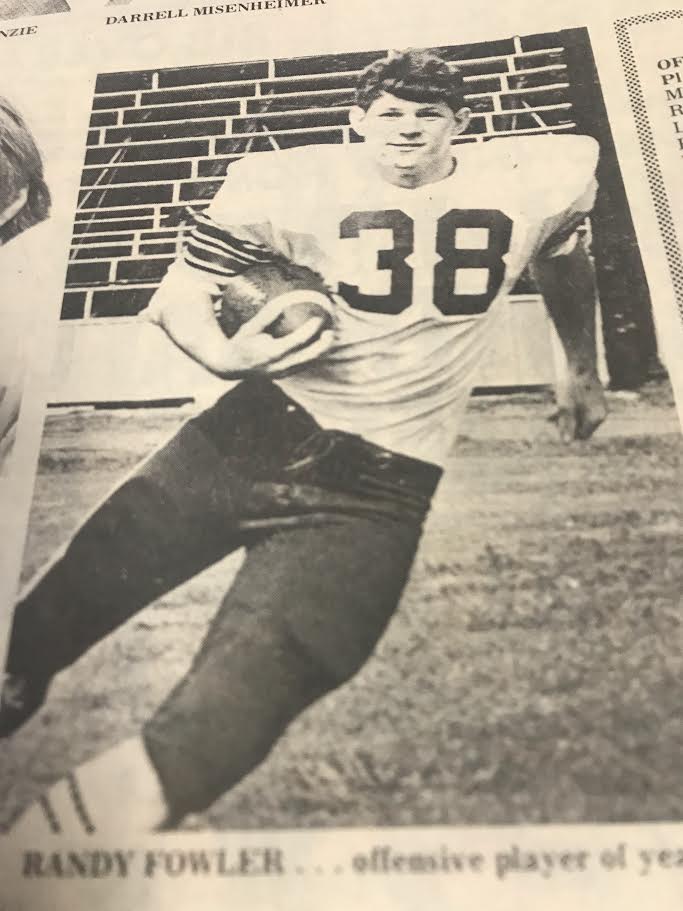

CHINA GROVE — Randy Fowler was a special football player for East Rowan 50 years ago.

“Special” probably doesn’t do Fowler justice because he was a force of nature for the Mustangs when he was a junior in 1974, playing for head coach W.A. Cline. Fowler wasn’t exceptionally big. Programs and newspaper clippings list him at either 5-foot-11 or 6-feet. His weight in the East Rowan booster club game programs that fans could buy for pocket change for the 8 p.m. games on Fridays was 193 pounds. The Salisbury Post listed Fowler at 186 after he was voted Rowan County Offensive Player of the Year in 1974.

But that 186 was all muscle, and it was mean, competitive muscle. And he was fast. Fowler was a track man and while he wasn’t quite as swift as teammate Kizer Sifford, who was recognized as the county’s fastest human, Fowler could sprint 100 yards in 1o seconds. The 10 flat 100 was the measure of speed merchants in the 1970s.

Clemson, Wake Forest, UNC and NC State were among the ACC schools that pursued Fowler and his running mate in the East backfield, Rick Vanhoy, with considerable gusto.

“Rick had a car and I didn’t and I rode with him to a lot of Saturday college games at UNC and Clemson when we were being recruited,” Fowler said.

Vanhoy and Fowler were friends as well as teammates, but Fowler will always wonder what would have happened had their roles been reversed. Vanhoy was the halfback, while Fowler was the fullback in East’s offense. Based on their size, that wasn’t by the book.

“I was a lot faster than Rick, and Rick (6-3, 215) was a lot bigger than I was,” Fowler said. “Those fullback yards are always the tough yards. I had some moves and I could cut on a dime, but usually I was running over guys. I’ve wondered how many yards I would have gotten running more of the outside plays. But I’m not questioning our coaching staff. What we did worked, and we ran the ball effectively, especially in 1974, even when everyone we played knew we were going to run the ball. We’d play South Rowan, and there were so many guys in the box, it was like they were standing around you in a huddle.”

Cline coached Fowler in track as well as football. Fowler had the necessary speed to lead off the 440-yard relay and 880-yard relay for the Mustang track and field team that won the county championship his senior year.

“Randy only knew one speed in anything he did,” Cline said. “Wide open.”

Fowler grew up the way a lot of boys used to grow up in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was raised on a family farm. The daily chores such as carrying water from springs and well and hauling wood for the stove, lugging the meat from slaughtered hogs, sound like insanely back-breaking labor to the youngsters of the day, but those tasks were not uncommon in the rural North Carolina of a half-century ago.

Fowler was performing wood/water duties from the time he was 5 years old. He was riding a combine at 7. He grew up fast.

“You had to be strong to do things like throwing hay bales into a stack in a barn loft,” Fowler said. “Farms are hard work.”

There was some time on weekends for games, usually tackle football in the yard with older, bigger, stronger cousins, so by the time Fowler arrived at Erwin Middle School, he was tough as a nail. He wanted to run the ball. They put him on defense, at first, but after a while he was playing both ways.

His first football season at East Rowan was in the fall of 1973. His coaches liked the energy and the speed. They installed him as a defensive end.

“I think I had four sacks one game,” Fowler said. “I ended up getting moved to running back with five games left in that season.”

East found something then. Officially, the Mustangs went 2-8 in 1973 — they forfeited two games they won on the field — but the Mustangs discovered a sophomore running back tandem filled with promise. Fowler had 454 yards on 80 carries. Vanhoy had 110 carries for 487.

Fowler spent summers with more hard work — bricklaying — that would improve his strength and his balance. It’s dificult work catching bricks while hanging on a roof and building chimneys.

“Balance is the most important thing a running back can have,” Fowler said. “Getting control of your body and understanding what your body can do. There were a lot of times, a defender took one of my legs out, but I was strong enough to stop my fall with one arm and just keep going. I can remember dog-paddling to the end zone for a touchdown against South Rowan.”

Most of Fowler’s fond football memories are from 1974. That would be the last championship season of Cline’s tenure. East also earned trophy-case hardware in 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971 and 1972 during those glory days.

“I did have a great season in 1974,” Fowler said. “The Post had a player of the week and I was the player of the week six times that year. But no running back has ever gotten a lot of yards without a good offensive line. We had a really strong line full of seniors.”

Three of the East offensive linemen were All-Rowan County in 1974 — huge tackle Darrell Misenheimer, 165-pound center Lloyd Stirewalt and guard Bobby Ribelin.

“The play for me was ‘Army 38,'” said Fowler, who wore the No. 38 jersey. “That was an up-the-gut play and I would follow the blocks of Misenheimer and Stirewalt and cut off them. I ran low to the ground, and if you tried to get lower than me, you were probably going to get a taste of my left forearm. Darrell would usually wear out two defenders, our opponent’s biggest guy and then their second-biggest guy, by halftime. Lloyd was a small lineman, but he was strong as an ox.”

In 1974, Fowler had 29 carries for 151 yards in a huge victory against North Davidson. He also had a kickoff return touchdown of 94 yards in that game. The ball took a funny bounce. It looked like it would go into the end zone, but instead it went to Fowler, who was suddenly off to the races. The Black Knights couldn’t catch him.

There was another play in that game that Cline kept running and re-running in the film room, counting broken tackles. Fowler says he broke nine on one play.

“Seems like the rest of you boys could have blocked the other two,” Cline said.

Fowler had 169 yards on 21 carries against Davie County, but the Mustangs somehow lost 18-14 in the regular-season finale.

“The refs let Davie get away with some stuff, “Fowler said. “They’d stop you, but they wouldn’t tackle you, and then two guys would try to pull your arm away from the football. The refs would rule it a fumble.”

The next week provided the most painful game of Fowler’s career. East played Mooresville at home in the first round of the WNCHSAA playoffs. East had trounced Mooresville 25-12 during the regular season and expected to do so again.

“It was a game we definitely should have won.” Fowler said of East’s 13-12 playoff defeat, the only playoff game he ever got to participate in “I’ve looked at the stats and we had 300 yards of offense and they had minus rushing yards and completed two passes. But the passes were touchdowns. Our last drive of that season should have won the game for us. Rick had come out with fluid on his knee, so it was just me running the ball every play. We got it down to their 7, first and goal. Then they got me for a loss on first down. On second down, we threw an interception, and that was the ballgame. I’ve always believed that if we’d run ‘Army 38’ I put the ball in the end zone behind Lloyd and Darrell, we win and we’re playing Salisbury the next week in the Piedmont Championship game. It just wasn’t meant to be.”

Instead, the Hornets smashed Mooresville. Then Salisbury beat Shelby for the WNCHSAA title.

Fowler was voted NPC Offensive Player of the Year as well as Rowan County Player of the Year. His effort against Mooresville put him over 1,000 yards for the season. He also was named “Bull of the Year” by the Post and the local steakhouse that sponsored those player of the week awards.

“Bull wasn’t my preferred nickname,” Fowler said. “My teammates called me ‘Freight Train.’ I did what I did that year despite missing a game and a half with an ankle injury. I didn’t play at all against South Iredell (a 6-6 tie).”

The Freight Train was still rolling in 1975, but it wasn’t quite the same as 1974. That fine offensive line had graduated. East had a super win against a strong North Davidson club, but the Mustangs settled for 6-4 and didn’t make the playoffs.

Fowler ran for 966 yards and was all-county, but it was a rough senior year for him. He tore ligaments in his ankle and separated a shoulder. The worst thing was taking a hit in the back of his neck. He remembers the impact knocked his helmet 15 yards away.

“Coach Cline got me a special helmet to wear, but I was never quite the same after that,” Fowler said. “Spinal injuries are rough.”

Fowler and Vanhoy both made the Shrine Bowl team in 1975, an incredible thing for two guys from the same backfield at a rural school

“Rick and I were roommates at the Holiday Inn near Memorial Stadium in Charlotte,” Fowler said. “We practiced on a field at North Meck, with holes everywhere, and it was a terrible weather week. We went at it hard in practice that week, and you’d get up with a mouthful of ice and mud whenever you got tackled. I hurt both groin muscles that week in practice doing up-downs, and I really shouldn’t have played in the game. I did play, so I can say I played in the Shrine Bowl, but I couldn’t perform the way I wanted to.”

Fowler signed with Wake Forest, as assistant coach Jim LaRue had done the best job recruiting him. Vanhoy signed with UNC.

“After the recruiting period, after I’d signed, Wake Forest dropped me,” Fowler said. “They’d signed another running back (James McDougald), who became the ACC Rookie of the Year in 1976. Teams had filled their recruiting quotas by the time they dropped me. I did have a chance to go to NC State, but Ted Brown had just had his great freshman year and looked like he’d be in the running for Heisman trophies. I didn’t want to sit on the bench.”

Catawba College seemed like a natural landing spot and a fallback plan for Fowler, and coach Warren Klawiter really wanted him.

“They offered a scholarship, and I did go to Catawba for a semester and went through drills with the team, but I was having a lot of pain,” Fowler said. “Terrible headaches from the neck injury. I just couldn’t do it.”

Two years later, Catawba coaches knocked on Fowler’s door again, but the body that had once been so powerful had let Fowler down. Football was over for him.

“People shouldn’t judge you, but they do,” he said. “A lot of people always wondered why I didn’t go play ACC football like Rick did. Believe me, I loved football more than anything in the world and I wanted with all my heart to play college football, but my body just didn’t let me. It happens. It just wasn’t meant to be.”

Fowler had talent as a machinist and engineer, went to Rowan Tech and aced his classes. He went to work at Cannon Mills Plant 16 on Highway 29. He rose quickly from fixer to foreman to supervisor to trouble-shooter and consultant. He solved mechanical problems and improved efficiency. He helped save jobs for as long as he could in the fading textile industry.

He retired 15 years ago. He’s 68 now — soon to be 69. He plays the drums for his church, and his deep faith has helped him handle the hard knocks that football handed him 50 years ago. Mustang memories are strong, but he doesn’t dwell on what might have been.

Fowler is facing another neck surgery soon. He’s hopeful it will alleviate some pain, so he can sleep better.

Still, the “Freight Train” is confident he can keep rolling for a long time.

“People shouldn’t judge you, but they do,” said Randy Fowler, who was a star for East Rowan football 50 years ago. “People want to know why you didn’t play college football. People

Wake Forest’s athletic history includes many highlights. But few memorable individual moments stand out as does that October afternoon in 1976 when a freshman running back in his first career start burst into prominence as a Demon Deacon. James McDougald’s work that day against Clemson – 249 yards rushing on 45 carries – remains one of the greatest performances in Wake history.

McDougald went on to attain 16 school records for rushing and scoring. More than 30 years after his final game, he remains first in career rushing attempts (880), second in rushing touchdowns (30) and second in rushing yards (3,865).

He is one of five Deacons to earn first-team All-ACC honors in three seasons (1976, 1977, 1979) and the only Deacon ever to lead the team in rushing four straight seasons. His brilliant career reached a climax when, as a senior, he helped Wake Forest to a 1979 Tangerine Bowl bid. On a team of excellent players, McDougald was named the Most Valuable. He also received the prestigious Arnold Palmer Award as the school’s top male athlete that year.

James McDougald was inducted into the Wake Forest University Sports Hall of Fame on January 18, 1992.